Node.js (JavaScript) performance tips

Published 24 May 2018

Historically, JavaScript has not been a performant language. It was originally designed for the browser and eventually it moved into the server-side mainstream with the introduction of node.js. Node.js uses Chrome’s JavaScript engine (V8) to execute code, and, as JavaScript was never great at CPU bound tasks it was designed around optimizing asynchronous / IO bound workloads.

Over time, that has all changed. Google’s relentless push for performance on V8 have made it a legitimate option for service side programming and CPU bound tasks. I’ve benchmarked the same application written in JavaScript and Scala and found they we’re more or less identical.

Unfortunately, JavaScript is a language with a lot of baggage, and when it comes to performance this means there can be some unexpected rough edges. There are some really good resources on pure JavaScript optimizations but they are mostly crowded out by advice on how to package, distribute and run JavaScript on the browser. Let’s look at some tips for pure JavaScript and node.js users.

1) Use async wisely

It’s a common misconception that node.js is single-threaded. The truth is that there are lots of threads in node.js, it’s just that the user land code (your code) is run on a single thread. In fact, the way node.js achieves good performance on IO bound tasks is by handing off anything waiting on IO to a thread pool so that the main thread can continue execution.

Using this knowledge we can shape our application to look like it is working in parallel by executing multiple asynchronous code blocks at the same time. I commonly use this when loading data out of a database, but it’s equally applicable for things like multiple HTTP requests.

const [data1, data2, data3] = await Promise.all([

someAsyncDataLoading1(),

someAsyncDataLoading2(),

someAsyncDataLoading3(),

]);

The code above will execute someAsyncDataLoading1() until an asynchronous call is made, at which point execution will continue on to someAsyncDataLoading2() and so on. Execution won’t continue until all the promises returned by all three functions have been resolved (or one throws an exception).

You can have async/await blocks inside each function call, so someAsyncDataLoading1() might look like:

async function someAsyncDataLoading1() {

const rows = await query("SELECT * FROM table");

return rows.map(row => new SomeObject(row.field1, row.field2));

}

As soon as query function is called, node.js will get an IO thread from the pool to wait for the response and it will yield the promise returned from the query function and then execution will continue on to the next item in the Promise.all list. If you are not sure how async/await is implemented with yield and generators have quick read of this explaination.

Being aware of how asynchronous code works under the hood allows us to maximize its potential. Move functions that hit asynchronous code sooner to the top of the pile in a Promise.all list, that way the main thread will move on to the next block and you will trigger the other asynchronous calls sooner.

2) Logical short circuits (lazy evaluation)

In JavaScript logical operators are evaluated from left to right (like all other languages) and they short-circuit, meaning that when the outcome of a logical statement has been decided execution stops. For example:

const alwaysTrue = () => true;

const alwaysFalse = () => false;

const resultA = alwaysTrue() || alwaysFalse();

const resultB = alwaysFalse() || alwaysTrue();

When resultA is evaluated alwaysTrue() returns true, as true || any is always true it doesn’t execute the alwaysFalse() function. It knows the outcome will be true.

It’s important to bear this in mind when constructing if statements. In this example:

const fastFunction = () => ...;

const normalFunction = () => ...;

const slowFunction = () => ...;

const resultA = fastFunction() || normalFunction() || slowFunction();

Functions should be ordered so that the cheaper ones execute fast, but you also need to factor in the likelihood of the functions returning true and shorting the circuit. If the normalFunction() isn’t too much slower than the fastFunction() and more likely to return true, put it to the front.

As an aside, JavaScript logical operators (||, &&, !) do not always return a boolean value. This means they can be used as part of an expression (something that returns a value) instead exclusively with statements (if, for, etc).

3) Avoid sparse arrays

Internally, V8 has many types of array but they fall in to one of two categories:

1) Holey arrays

2) Packed arrays

A holey array is “sparse” and has gaps in between elements, whereas packed arrays have no gaps.

const sparse = [];

sparse[10] = "a";

sparse[15] = "b";

sparse[50] = "c";

const packed = [];

sparse[0] = "a";

sparse[1] = "b";

sparse[2] = "c";

const packed2 = ["a", "b", "c"];

Always try to use a packed array where possible as there are many optimizations that V8 can only perform on packed arrays.

Depending on how you create your array, it’s type my be converted between holey and packed, but this has a cost and should also be avoided. This example, shamelessly lifted from V8’s blog, demonstrates the conversions:

const array = new Array(3);

// The array is sparse at this point, so it gets marked as

// `HOLEY_SMI_ELEMENTS`, i.e. the most specific possibility given

// the current information.

array[0] = 'a';

// Hold up, that’s a string instead of a small integer… So the kind

// transitions to `HOLEY_ELEMENTS`.

array[1] = 'b';

array[2] = 'c';

// At this point, all three positions in the array are filled, so

// the array is packed (i.e. no longer sparse). However, we cannot

// transition to a more specific kind such as `PACKED_ELEMENTS`. The

// elements kind remains `HOLEY_ELEMENTS`.

If you need to index values that are non sequential you should use an object:

const index = {};

index["10"] = "a";

index["15"] = "b";

index["50"] = "c";

const index2 = {

"10": "a",

"15": "b",

"50": "c"

}

Note that the indexes have been converted to strings to ensure that V8 creates an object.

4) A little bit of mutability never hurt anyone

With the rise of functional programming in the JavaScript world many people are opting for more immutable data structures. On the whole this is a good thing, but it should be used carefully as it can impact performance. This is one of the reasons that I typically advise people not to use libraries like immutable.js - if you don’t want to mutate your data structures, then don’t.

Taking an example of push() vs concat():

const mutable = [];

let immutable = [];

const items = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10];

for (let i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

mutable.push(...items);

}

for (let i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

immutable = immutable.concat(items);

}

The push() variant will outperform the concat() every time. There is a more detailed jsperf available.

It’s important to remember that shared mutable state is the enemy, local mutable state is mostly fine.

5) Reverse your queues

If you find yourself using a lot of queue structures then it’s worth noting that pop() is faster than shift()

array pop vs shift for queues so it can be beneficial to reverse your queue and use pop().

The reason for the performance difference is that after shift() takes the item off the beginning of the array, it needs to re-index the entire array. With a large array this can be very expensive.

6) Avoid delete

Despite many recent improvements in V8, delete is still a keyword to avoid. Using delete to remove a property from an object will switch the objects internal representation to a slow object, killing many optimizations.

Avoiding delete can be tricky. Setting the propery to null or undefined is common, and faster, but the key will still exist in the object.

7) Caching and memoization

Performance is often a trade off between CPU time and memory usage. Memory is cheap, so where possible make use of it to avoid repetitive calculations.

Memoization is handy technique where the return value of a function can be cached for a given set of inputs. It’s a cheap win for CPU bound tasks and there are many helpful libraries available.

8) Avoid scanning large arrays

Another way to trade CPU time for memory is to convert arrays into objects to avoid scanning every element:

const items = ["apple", "pear", "banana", ...];

const index = items.reduce((p, c) => {

p[c] = true;

return p;

}, {});

const slowFind = items.includes("pear"); // o(n)

const fastFind = index["pear"]; // o(1)

9) Avoid garbage collection

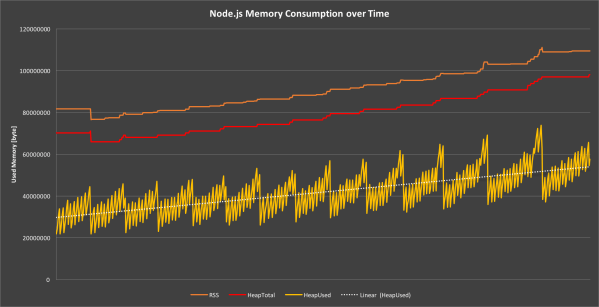

The flip side of the CPU/memory coin is that if you use too much you will invoke the garbage collector, which will halt execution of your application until it is done. V8 employs two different strategies for garbage collection:

- Scavenge: fast but incomplete

- Mark-Sweep: relatively slow but frees all non-referenced memory

Daniel Khan’s post on garbage collection covers them in more detail but you can see the impact of each type of garbage collection from this diagram:

Contrary to points 7 and 8 you want to make sure you don’t allocate large amounts of memory only to free it again later. If you need caching and memoization, make sure the benefit of having them outweighs the potential cost. Memoizing trivial functions is often not worth the memory cost as V8 might inline/optimize the function anyway.

10) Multi-core process/clusters

As explained above node.js is not designed to support threaded application code (although there is a patch on the way), the only alternative is to create a new process. Node.js comes with a relatively simple child_process library that has two methods of creating new processes: spawn and exec. To stream data use spawn to set up a worker with message passing, use exec.

Unlike threads, there is no shared memory between processes so you have to do a cold boot of an entirely new node.js instance every time you spawn / exec meaning that it’s not feasible to do for some pieces of work, or tasks that need to transfer large data structures.

Advice you can ignore

One of the problems of writing performance tips for V8 is that it’s a moving target. The V8 team will often find new optimizations rendering some tips obsolete. Here are some tips that used to be true but no longer are, as of node 10.x / V8 6.6:

Inline functions

This advice dates back to ye-olde C times when you could mark a function as inline and the compiler would copy paste the code in. Essentially it avoids a CPU context switch by avoiding the function call. This no longer applies (and may never have applied) because V8 is a JIT compiler is very good at choosing what to inline and what not to inline. There are options to configure how much will get inlined but 99% you don’t need to worry about this.

Avoid for…of

In previous versions of V8 for...of was less optimized than for...in and traditional for loops. As of V8 6.6 there is still a small difference but it’s not significant enough to worry about.

Function comments impact inlining

This article outlines a scenario where the length of a comment impacts the size of a function, and whether it will be inlined by V8. This issue was actually fixed in V8 5.9 and there are some handy benchmarks. It is also possible to increase size of the function that will be inlined using the --max_inlined_source_size option.

How to keep up-to-date

Node.js performance is a constantly moving target. The two best resources are the V8 blog and the node.js blog and of course, always measure the impact of any optimizations you make as they don’t always do what you expect them to.